Gilbert Soto is the interstate compact administrator for the State of New Jersey Department of Children and Families and a graduate of the MPLD program at AdoptUSKids. He’s been working in child welfare for more than 20 years.

Like all MPLD fellows, Gilbert completed an action research project addressing a pressing need in his workplace. We talked with Gilbert about his project and how he benefited from participating in the leadership program.

What challenge did your action research project address?

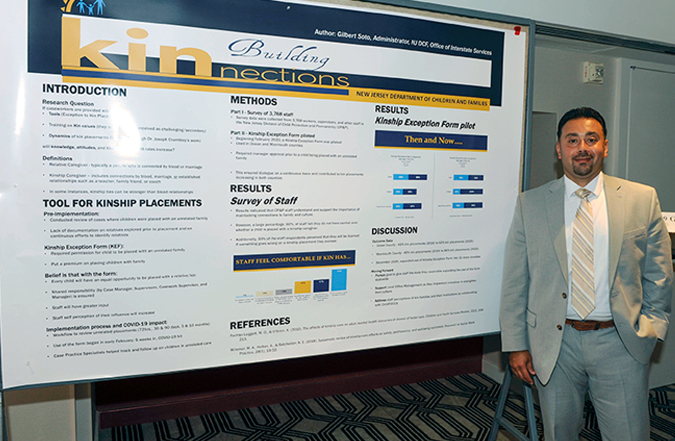

When I was accepted into the MPLD program, I was the kinship program manager for New Jersey DCF, and I chose a topic that aligned with my job responsibilities. Through my research project, I hoped to understand the barriers to kinship placements and—ultimately—have more children placed with kin.

I also wanted to understand how children’s race affected kinship placements.

How did you pick your project?

I’ve been doing this work for 20 years, and during that time, there’s been a growing awareness of how important it is to keep kids connected to their culture. When we talk about culture in that sense, we’re usually talking about kids’ race and ethnicity. But within that bigger culture is the little culture that makes a family. That culture can be maintained if children stay with their relatives.

I understand the value of those connections on a personal level, because my mom was raised by her relatives, and they are all near and dear to me.

How did you investigate the role that children’s race played in kinship placements?

I focused on two NJ counties that did well with kinship placements but struggled with placing children of color with family. One county (Ocean) had a low rate of kinship placements of African American children. The second (Monmouth) had low kinship placement rates for Hispanic children.

A big part of my project involved surveying staff to get a sense of what was holding them back from placing kids with relatives. Did they feel safe and confident in doing so? Were they making decisions based on children’s race?

I was fortunate to have the assistance of our research office in developing and disseminating the survey as well as in analyzing the results. I can’t thank them enough for their support. We received an outstanding response rate to the survey: more than 3,600 people responded—representing 77 percent of the staff—and answered every question! I think the timing—just before everything shutdown for COVID—and some valuable incentives helped. The results of that survey enabled me to identify challenges and propose solutions.

What challenges did you identify?

Interestingly, though children of color were being placed with kin at lower rates in the counties I focused on, workers did not appear to be biased by color when making placement decisions. We were able to determine this by giving workers two photos—one of a white child and one of Black child—and describing the same scenario about each child and their placement options. Workers then had to answer a series of question about where the child should be placed based on what they saw. Their responses did not vary by the color of the child.

The biggest factor that seemed to be affecting workers’ decision was risk aversion.

In my surveys, two-thirds of workers reported that they had no control over the decision to place children with relatives, and one-third said they feared they would be blamed if something went wrong.

Workers were holding relatives to the same standards as unrelated foster parents. Which, on the surface, sounds reasonable. But you cannot look at family that way. They are not coming in prepared and trained. They are getting a phone call saying: “We have little Johnny. Can you help?”

And solutions?

Our big focus going forward has been identifying ways to make staff feel safe in their decision-making process. And that means involving and collaborating with staff at all levels.

One tool that, quite frankly, we stole from Tennessee is a “kin exception request” form. Using this form, the worker is able to document that they did their due diligence, note any areas where the relative’s home may not meet non-relative foster parent licensing standards, make a recommendation, and obtain and document their manager’s approval. This process makes the licensing process more flexible and addresses the risk-aversion aspect of the problem, which I think is the biggest barrier.

How do you measure success?

The counties I worked with—and others in the state—started improving before my project was complete simply by being made aware of the problem and taking steps to evaluate their decision-making process. By the end of the research period, Ocean County had gone from 38 percent placement of African American children with relatives to 67 percent kinship care placement. Monmouth went from 31 percent to 100 percent placement of Hispanic children, and both counties have been able to maintain a range of 32-95 percent over the last year.

As a state, overall, now we’re placing around 60 percent of children with relatives. It’s a real testament to the strength of our leadership and our staff buy-in.

You’ve been doing this work for more than 20 years. What attracted you to the field?

Sounds cliché, but I wanted to help others. That really was the main reason. I learned to value helping community from my mom, who has always worked in the social service field. She still does!

I’ve kind of done just about everything in the foster care world. I started out doing casework and then spent 15 or so years facilitating placements and recruiting families. In the last seven or eight years, I moved into administration and supervision. It’s been one heck of a journey!

I recently accepted the position of administrator over our Interstate Compact Office. I’ve got a lot to learn in that role, and the skills I acquired through participating in MPLD and the connections I made are going to help a lot.

What were the biggest benefits of participating in the MPLD program?

Before MPLD, I’d been in management positions for several years. I’d picked up pointers from colleagues and leaders I admired along the way, but I never had any formal leadership training.

Participating in MPLD gave me an opportunity to build on those skills and get a bigger picture. I learned not just about being a leader, but about being a transformational leader. Now I realize that my role is not only to lead, it is also to identify and nurture individuals who can come up behind me and to leave my position in a better place than I found it. Because intentionally or not, that will be my legacy.